The headline — Police probe opened into rumours of unsafe tap water in Paris — raised hopes that nuclear operators might finally be held accountable for what appears to be routine radioactive contamination of drinking water in France.

News stories had circulated after a French radiological testing laboratory published findings on June 17, 2019, that more than six million French residents were drinking water contaminated with tritium released by the country’s nuclear power plants and other nuclear installations.

The laboratory — L’association pour le contrôle de la radioactivité dans l’Ouest or ACRO — raised the alarm because, it said, the presence of tritium implied there could be other radioactive isotopes in the water as well. None of the tritium levels they measured on this occasion, exceeded those French health authorities have established as “safe”, but research in the past has found higher levels, especially in groundwater, rivers and streams.

The Tricastin nuclear site — source of multiple leaks and radioactive releases over decades. (Creative Commons/xklima)

That “acceptable” level is 100 Becquerels per liter, not quite as arbitrary as the shocking 10,000 Bq/L level set by the World Health Organization, in thrall to the nuclear power-promoting International Atomic Energy Agency through a 1959 agreement.

The cities affected included Paris and its suburbs, and other large population areas in the Loire and Vienne regions of France such Orléans, Tours and Nantes.

Unsurprisingly, the story spread like wildfire, especially across social media, causing alarm among residents in the communities cited — 268 in all.

But the police investigation in Paris was not of EDF, the country’s chief nuclear facility operator. It was to root out fear-mongering purveyors of “fake news” among the citizenry who, according to the French state, were unnecessarily spreading panic among the populace by claiming drinking water containing tritium is unsafe.

It is.

The independent radiological testing lab CRIIRAD (Commission for Independent Research and Information on Radioactivity) denounced what it called the “trivialization of tritium contamination” and warned French citizens not to be lulled by the 100 Bq/L levels set by the authorities and especially not by the WHO’s 10,000 Bq/L standard. CRIIRAD said the level for tritium in drinking water should be set between 10 and 30 Bq/L.

For context, in our report, Leak First, Fix Later, we noted that the “naturally occurring” levels of tritium found in surface and groundwater is, at its highest, 1 Bq/l. Therefore, tritium is almost non-existent in water in nature.

To CRIIRAD, it is therefore all the more outrageous that that the levels for radiological contamination in France are set at “more than 100 times higher than the maximum allowed for chemical carcinogens.”

Tritium is radioactive hydrogen and is therefore assimilated by all living things as water. It has a half life of 12.3 years. It is produced in huge quantities in nuclear reactor cores, then released into the environment as a gas or in liquid discharges. Tritium cannot be filtered out of water and tritium released into the air can return in rainfall. All nuclear power plants release tritium, and nuclear reprocessing facilities — such as the one at La Hague on the French north coast — release even larger amounts.

These releases, including into rivers, streams and the sea, are regulated by authorities but, as CRIIRAD points out, at levels that are not so much safe as unavoidable, effectively granting nuclear installations “permission to pollute.”

“The liquid and atmospheric releases of tritium cause contamination of the air, water, the aquatic and terrestrial environment and the food chain,” wrote CRIIRAD in a statement put out after the tritiated drinking water news broke.

When rumors began to fly that drinking tap water had been banned, authorities quickly stepped in to “reassure” people that the levels of tritium in the water — already not actually safe according to CRIIRAD — were of no concern.

The criminality of nuclear plants across France releasing huge amounts of tritium into the environment was quickly turned on its head. Instead, in a sinister but not entirely unpredictable turn of events, given that France is a nuclear state, it would be ordinary citizens who would be committing a “crime” if they were found to be “publicizing, spreading and reproducing false information intended to cause public disorder,” according to an AFP article.

In reality, there was genuine cause for concern. ACRO had found levels of tritium in drinking water at 30 Bq/L on five occasions, then at 55 Bq/L and finally at 310 Bq/L in the Loire river.

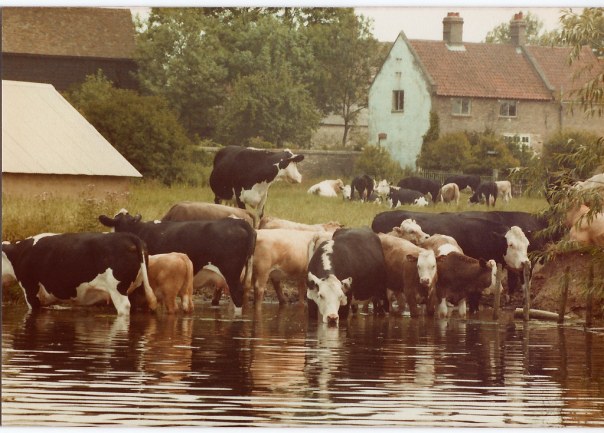

Picture entitled “Water makes milk.” In France, is that milk radioactively contaminated? (Photo: Graham Knott/Creative Commons)

But drinking tritiated water is not the end of the story — or the danger. Even though tritiated water may pass through the human body in about 10 days, about 10% of it binds organically inside the body. Organically bound tritium remains in the body for far longer than free tritium. According to CRIIRAD, this means that beta radiation from tritium can endure inside the body for years, causing chromosomal mutations, cancers and genetic mutations.

Tritium also binds organically to organisms in the environment such as aquatic plants present in rivers and streams into which nuclear facilities release tritiated water, or crops irrigated using water contaminated with tritium. These are in turn ingested by animals and humans — setting in motion tritium’s journey up the food chain […]

via When your beverage of choice is tritium

Exclusive: CPEC master plan revealed

Exclusive: CPEC master plan revealed