By Rima Najjar

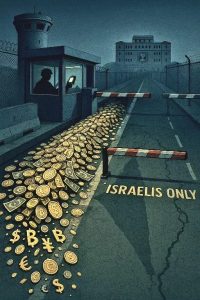

How Israel Became the Palestinian Tax Collector

The fiscal trap Palestinians live under today did not arise organically; it was engineered, codified, and then left untouched for thirty years. Its blueprint is the 1994 Paris Protocol, the economic annex to the Oslo Accords, which was marketed at the time as a temporary framework for a transitional period leading toward Palestinian sovereignty.

In reality, it created a one-way customs union in which Israel retained full control over borders, ports, import channels, and the taxes generated from nearly all goods entering the West Bank and Gaza. Under this arrangement, Israel collects VAT, customs duties, import taxes, port fees, and fuel excise charges on behalf of Palestinians, aggregates them into “clearance revenues,” and then transfers them to the Palestinian Authority — minus whatever deductions it unilaterally decides to impose. These revenues now make up the majority of the PA’s budget and are the financial core around which Palestinian governance has been forced to revolve.

[…]

Even highly restricted aid shipments, routed through layers of Israeli bureaucracy, pass through the same fiscal machinery that treats Gaza not as a humanitarian catastrophe but as a taxable market. The perversity deepens: Israel has frozen Gaza’s entire share of its own clearance revenues, diverting or withholding funds generated from imports destined for the Strip. Gaza’s hospitals run out of fuel while the taxes generated from that very fuel accumulate under Israeli control or sit in foreign escrow.

[…]

The same mechanism operates in the West Bank, only with less visible violence. A factory in Hebron importing machinery from China pays Israeli customs duties. A supermarket in Jenin stocking Israeli dairy products generates VAT for Israel before any share is transferred to the PA. Fuel purchases — one of the largest revenue sources — are taxed entirely at Israeli rates. In each case, Palestinians do not control their tax base.

They receive it as a monthly allowance, released or withheld depending on Israel’s political calculations. For decades, Israel portrayed this as administrative necessity: because it controlled the borders, it had to collect the taxes. But over time, the mechanism became a political pressure tool.

[…]

Since October 2023, the situation sharply deteriorated. Israel froze Gaza-related revenue outright, dragging out clearance transfers for weeks or months, and withholding far larger sums from the West Bank portion. The PA’s fiscal capacity collapsed; salaries became partial, delayed, or split into unpredictable installments.

Ministries cut services. Municipalities closed departments or deferred maintenance. Universities and hospitals sank into debt spirals. The PA could not plan more than thirty days ahead because it no longer knew if or when Israel would release the funds. By early 2024, the Authority had become a government whose operational budget was effectively determined in Jerusalem — in the Israeli Ministry of Finance, not in Ramallah.

But the structural dependency designed by the Paris Protocol runs even deeper than monthly cash transfers. Because Palestinians are locked into the Israeli VAT system, they inherit Israeli prices without Israeli incomes. They pay Israeli fuel tariffs that inflate transportation and electricity costs.

Their banks rely on Israeli clearinghouses. Their imports are routed through Israeli ports that impose fees at every stage. The customs union acts as an economic occupation layered beneath the military one: Palestinians must purchase within an Israeli cost structure even as they are denied sovereign tools — monetary policy, customs borders, independent import regimes — to shape that structure to their needs.

The PA has no control over its external borders, no independent central bank, no control over its main revenue streams, and no authority to regulate the cost of the goods on which its own tax revenues depend. It survives only if the colonizer transfers the funds it collected from the colonized.

This is the tax cage: a colonizer that collects your taxes; a government that depends on the colonizer to survive; and a public that pays the cost through inflated prices, weakened purchasing power, and delayed salaries. The extraordinary part is not that this architecture was built in the 1990s, but that it was kept in place for three decades — even as the PA’s political legitimacy eroded, even as Israel hardened its control, and even as the system cannibalized itself after October 2023.

[…]

The West Bank in Slow-Motion Strangulation

Gaza reveals the tax cage at its most lethal extreme. The West Bank reveals the same mechanism running in slow motion — less spectacular, but no less suffocating.

Salaries alone consume between half and nearly two-thirds of the PA’s entire budget, a figure considered unsustainably high by international standards but inevitable in an economy fragmented by occupation and denied sovereign revenue sources. Because Israel-controlled clearance revenues — VAT, customs duties, and import taxes collected at Israeli ports — constitute about 60 to 70 percent of the PA’s total income, even a single delayed transfer can jeopardize payroll. There are no sovereign reserves to fall back on, no independent monetary policy, and no ability to borrow internationally without Israel’s permission. The result is a fiscal architecture designed for permanent fragility.

A fourth layer is now emerging: the Trump-Netanyahu strategic blueprintfor the West Bank and post-war Gaza. Under this vision, the PA is not meant to be strengthened. It is meant to be preserved precisely in its current weakened state — an administrative entity that manages civilian affairs but lacks the fiscal or political autonomy to challenge Israeli control. The PA is expected to be strong enough to administer, too weak to resist; responsible for civilians, irrelevant to national strategy; sufficiently functional to relieve Israel of direct governance, perpetually dependent on Israel’s tax transfers to survive. This is not a new architecture. It is the existing system, fortified.

Yet even inside this tightening structure, cracks have widened — cracks born of necessity, crisis, and improvisation. Communities have developed survival economies anchored in family networks, zakat committees, cooperatives, and local production. Municipalities have learned to rely on local revenue when Ramallah cannot deliver.

Universities, hospitals, and large NGOs have built financial ecosystems that bypass the PA entirely. Boycotts and shifts in consumption patterns have begun to weaken Israeli-taxed imports. And the PA itself retains dormant legal and administrative tools it has never mobilized: challenging the Paris Protocol, demanding third-party oversight of clearance revenues, devolving power to municipalities, restructuring its security posture, and cultivating alternative revenue streams.

What Palestinians Are Already Doing: Cracks in the Cage

[…]

The first and most immediate site of autonomy is at the community level, particularly in the production and consumption of food. Every time a Palestinian family buys a locally made staple instead of an Israeli or imported one, VAT and customs revenue shrink along the Israeli-controlled pipeline.

This is not an ideological aspiration but a documented trend, especially since 2019.

In Qabalan, a women-led agrifood cooperative that received technical support from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization upgraded its facilities and now produces freekeh, wheat products, pastries, and frozen sambousek distributed in Ramallah, Nablus, and Jenin.

In Dura, south of Hebron, a cooperative of twenty women has built a two-story production facility with an annual operating budget of roughly two million shekels, supplying the West Bank with maftoul, mulukhiyah, jams, and grape molasses.

In nearby Tafuh, the al-Nahda cooperative runs a bakery generating about 25,000 shekels in monthly sales, while in al-Aqbabah the Beit Emmaus cooperative increased its frozen vegetable output fourfold between 2019 and 2021 and now employs twenty-five women who each earn about 1,500 shekels per month — providing a local alternative to heavily taxed imported frozen goods.

In Kufr al-Deek in the Salfit governorate, the al-Zaytouna cooperative produces bread, pickled vegetables, olives, herbs, and maftoul for school canteens and supermarkets, replacing products that previously passed through Israeli wholesalers and customs posts. These examples are not boutique experiments. They are manufacturing and processing operations producing the everyday staples — bread, dairy, freekeh, vegetables, jams — that form the core of Palestinian diets.

The wider food manufacturing sector confirms that these cases are part of a larger structural trend. A 2017 survey by the Palestinian Ministry of National Economy found that local producers already supply about 57 percent of dairy consumed in the West Bank, more than half of processed fruits and vegetables, and roughly 80 percent of all bakery products. The sector includes over 560 registered enterprises and comprises nearly a fifth of the entire Palestinian manufacturing base.

These numbers demonstrate that Palestinians already dominate essential food categories — and that scaling up the cooperatives emerging across the West Bank would further shift consumption away from Israeli-taxed products.

After October 7, 2023, this shift accelerated. Boycotts of Israeli and U.S.-linked brands produced measurable market changes: the Palestinian soft drink “Chat Cola,” produced in Salfit, reported more than a 40 percent surge in sales; two KFC branches in Ramallah closed after demand collapsed; and supermarkets in Ramallah, Nablus, and Jenin noted significant increases in sales of local snacks, beverages, and household goods.

Palestinian Customs Authority data cited by Al-Jazeera showed declines in Israeli imports in categories like chips, soft drinks, and cleaning products. Academic work from 2023 analyzing the relationship between boycott campaigns and import patterns confirmed statistically that periods of intensified boycott correlate with reduced Israeli imports and increased local production in key food sectors. Together, these trends form a quiet but material form of economic resistance: local production plus coordinated boycotts equals a shrinking taxable frontier.

The second domain where cracks in the tax cage appear is at the level of institutions and municipalities, which have long operated with degrees of autonomy simply because they have had to. When the PA cannot pay salaries or transfer funds, many municipalities continue functioning by relying on local revenue streams that never pass through Ramallah. Nablus has repeatedly used water-billing income to cover operational costs during PA liquidity crises.

[…]

Major Palestinian institutions also function largely outside the PA’s fiscal architecture. Universities such as Birzeit, An-Najah, Bethlehem, and Hebron depend primarily on tuition, international grants, and diaspora donations — not PA transfers.

Hospitals such as Al-Ahli, St. Joseph, and Augusta Victoria are funded by church networks, international NGOs, and community fundraising.

[…]

A third layer of autonomy is the network of parallel services that emerges during Israeli raids and curfews. In Jenin, Tulkarm, Nablus, and parts of Ramallah and Bethlehem, communities have repeatedly organized ad hoc medical response teams, field clinics, food distribution networks, neighborhood patrols, and transportation arrangements. These systems spring up because the formal ones are incapacitated or barred by the occupation. That they work — improvisationally but effectively — underscores a deeper truth: Palestinian society already governs itself under stress, and often does so more coherently than the PA can when dependent on Israeli revenue flows.

[…]

What ties all these examples together is that none are speculative.Palestinians already have functioning micro-economies that operate outside Israeli tax capture; institutions already bypass the PA’s revenue shortages; municipalities already keep essential services running when Ramallah is insolvent; and the PA already possesses legal and administrative levers it has simply never used. The autonomy Palestinians need is not a distant aspiration. It already exists in embryonic form across the West Bank. The task is to expand and coordinate these structures into a deliberate strategy — not as a substitute for liberation, but as its foundation.

These practices are impressive, but they are usually treated as mere “coping.” History shows something far more radical: every time the formal fiscal pipeline has been completely cut, Palestinian society has not collapsed — it has reorganized itself.

[…]

The most severe test came after October 7, 2023, when Israel froze Gaza’s entire share of the clearance revenues and delivered only fragments of the West Bank’s portion. For over a year, the PA lurched between partial salaries, delayed salaries, and no salaries. Yet the West Bank did not descend into chaos.

What emerged instead was what many Palestinians have begun to call a “shadow social economy”: neighborhood funds that purchased food for the poorest; agricultural collectives that distributed produce directly; youth groups that organized emergency medical response during raids; and diaspora remittances that surged quietly into family accounts.

[…]

Via https://www.globalresearch.ca/palestinians-can-recover-autonomy-under-occupation/5907445

Pingback: ISRAELI THEFT OF PALESTINE TAX AND REVENUES KEEPS THE ROGUE STATE RICH | Worldtruth